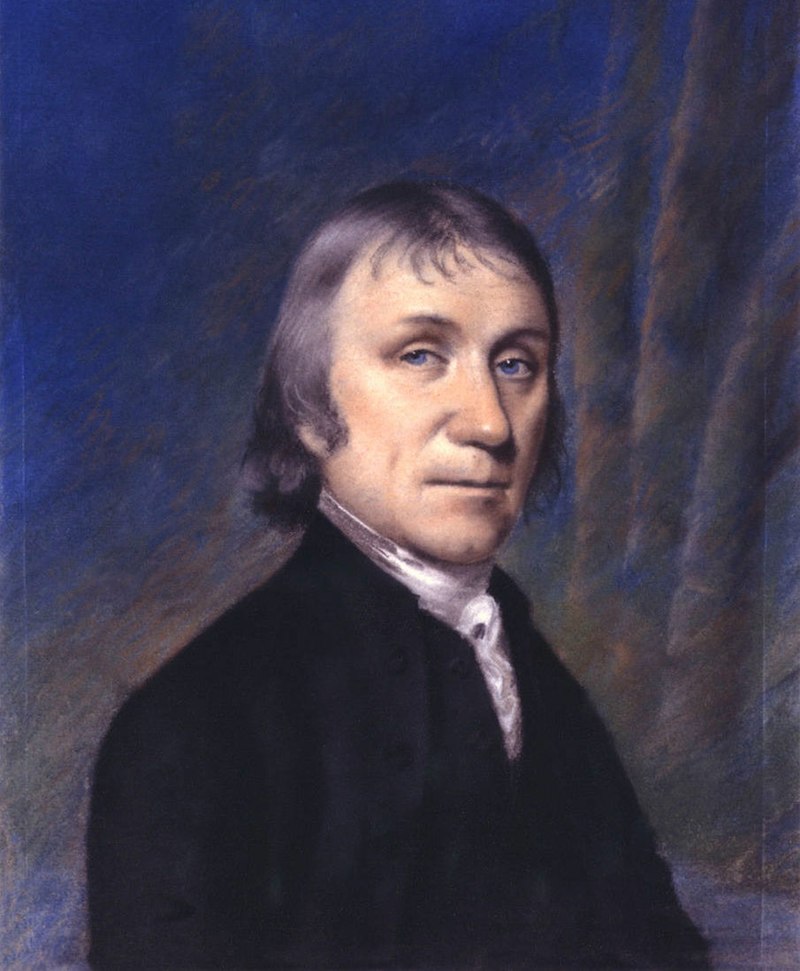

I am once again

tackling a figure whose work lies on the borders of philosophy and

science. I haven't read any one book from him, but instead, I have

investigated a selection, the title of which (Priestley on science,

philosophy and politics) reflects the variety of the thinker's

interests. Because Priestley was also interested of religion, one

might say that he played altogether four different roles.

Starting first from

the role of a scientific investigator, we may note that Priestely is

famous as one of the first people to separate oxygen from air. But

Priestley's discovery is an important indication how different it is

to do an experiment and to interpret it correctly, as he did not

believe he had found a new element – instead, he thought he had

managed to purify air from phlogiston, the element that supposedly

caused all phenomena involving fire. Priestely quickly noted that

this purified air was more invigorating than ordinary air and he also

noted that plants appeared to emanate such air.

In addition to

dabbling with scientific experiments, Priestly was also a historian

of science and worked on an history of electrical studies. Still,

perhaps most interesting work of Priestely on the topic of science

are his plans for systematising scientific research. Priestly

suggests that instead of founding huge societies responsible for all

kinds of scientific study, there should be many small societies

specialised for a small subfield in science and responsible for

collecting funding for that field. In effect, Priestly is suggesting

an idea common these days, that universities should concentrate their

research on their strong areas.

Priestley's

innovative skills were not restricted to mere research politics, but

he was, secondly, an eager political thinker. His model of good

society was clearly based on United States of America, as he was a

stout defender of republicanism and demanded the right of citizens to

have an extended field of action, in which state should have no say

at all – Priestly goes even so far as to suggest that education

should be no business of the state. Furthermore, Priestley speaks

vehemently against any privileged class or nobility, except in case

of such a class serving the needs of state. And while Priestley did

condemn rebellions, he also noted that fight against tyranny was no

true rebellion. In line with Priestley's rather Republican ideal of

society is his insistence that criminals should be punished hardly,

in order to deter anyone from committing a crime. Ironically,

Priestly congratulates USA of not being a colonial power and of

never falling into a civil war – a mere century would have proven

him wrong.

An important part of

Priestley's liberal ideal of state is a demand that all religious

sects should be tolerated. This is an important element in his third

role as religious thinker. Priestley was a unitarian, who thought

that Christ did not have a divine nature. Indeed, his philosophical

views went even farther away from the traditional religious views. For

instance, Priestly denied the possibility of spontaneously working

will, but insisted that all actions require some motive – even the

act of going against a motive is never unmotivated. Somewhat

surprisingly, in addition to basing this thesis on the universal

validity of causal principle, Priestley also uses a religious

argument – God could not foresee things ahead, if the events of the

world would not work in a strictly deterministic manner. Furthermore,

he also notes that morals would not work without complete

determinism, since a randomly acting person could not be improved in

any manner – she could always accidentally act in a completely

different manner.

In addition to being

a determinist, Priestly was also a materialist. Or, to put it better,

he did not believe that there was any wide cleft between material and

spiritual phenomena. Matter was not a plenuum or completely solid,

but must have been full of emptyness, since it e.g. could be a medium

for movement of light. And if matter was really not material in the

brute sense of the word, Priestley argued, why could we not say that

so-called soul is also made of matter?